Loading...

Loading...

This is a continuation of the Part 1 of the blog

Not all stories with a character with disability can be a good one. Just like any good story, it should have a compelling plot, engaging characters with authentic and realistic representations of lives and experiences that leave an indelible mark in the minds of readers.

Moreover, we hope it has what Dyches et al. (2011) call “positive portrayal”, where –

This portrayal could be through the descriptions, illustrations, characterization and the incidents and interactions the creators choose to include in the story. No one story or book may include all these aspects, but the hope is for including more protagonists or characters with disability that are treated respectfully in the narrative. In our conversations, we explored children’s responses to both the story as well as to these aspects of representation; and how they interacted with children’s own beliefs about people with different abilities.

Children loved the stories across the board, even though the favourites tended to vary quite a lot. Children recognized that these were all good, engaging stories with or without the characters with disabilities. Children in a group went on to say – ‘In Catch the Cat, they did not need to show a wheelchair at all, it was all about the love for the cat. It could have been any other challenge’. Similarly, when a set of children were asked to share how they might extend the story of Kanna Panna further, most of them had focused on the theme of friendship between Kanna and Murugan and on Kanna’s increasing confidence’. This is a huge win – children responding positively to stories rather than feeling that they are inauthentic or forced narratives set around characters with disability (Nasatir & Horn, 2003). According to Pennell, Wollak and Koppenhaver (2018), “… [We need to] include stories of characters with disabilities engaged in exciting adventures or fully engaged in life.”

Another aspect of the books that made these books accessible and enjoyable for children is how successfully they employed humour as the main narrative device in telling the stories. Humour seems to have helped the readers to access the lives of the others more easily and made talking about difficult issues easier. When done respectfully, depicting people with disabilities having fun presents a more complete picture of their rich and varied lives and personalities than when books only talk about their struggles and isolation.

Humour also helps bring to fore the commonalities in our experiences. “I like that she is having fun with her friends,” said yet another child about Dip Dip in Catch that cat! Kids loved Dip Dip’s naughtiness and most of them had overlooked that she was wheelchair-bound – so taken in by all the mischievous things she was doing. When they finally realize that Dip Dip uses a wheelchair to get around, one kid said, “How is that? She is just like any kid running around,” genuinely confused.

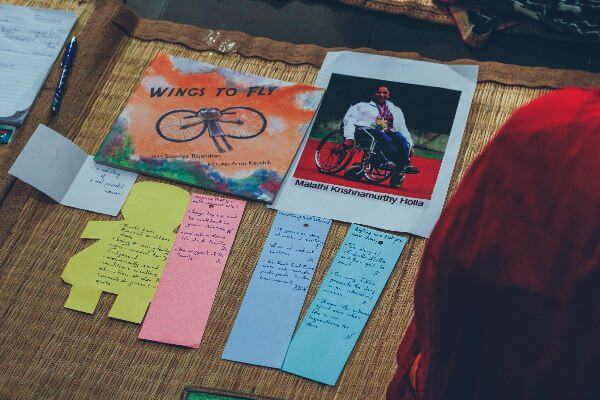

This does not mean that there is no space in children’s literature for more serious narratives around the experience of disability. One of the most popular books of the present set is Wings to Fly, a biographical account of para-athlete Malathi Holla’s life. It is a stirring and inspiring tale and left the readers with the positive message of overcoming obstacles through strong will and hard work, making it the favourite book for many children. While the message that disability does not mean inability may seem clichéd, the particular treatment it received in this book seems to have made it especially powerful for children with disabilities. One of the members in our group discussions was a spirited girl with cerebral palsy (CP) who ensured that all her points were heard, feverishly jotting down opinions and thoughts with her mother holding down her hand on the notebook. She felt very strongly about Malathi’s story, and this book may have offered her an exciting, new perspective while also mirroring her own experiences –

‘I like Wings to Fly because it talks about challenges that Malathi faces in her life. It resonates with my life. I can imagine how difficult it must be for Malathi to fight for her rights, and I want to win all the races of my life, like her’

It is also crucial to show how people with different abilities interact with the people and society around them, how their actions and contributions are valued and that they have a sense of self and agency in resolving their problems (Dyches et al, 2006). This was an important aspect for us – the characters with disability in our books are shown to take initiative, make decisions, offer help, initiate action. A few examples: Dip Dip offering to help her able-bodied friend look for her cat; her wheeling around the neighbourhood asking strangers about the missing cat without anyone so much as batting an eyelid; Malathi deciding to show that she is more than her disability and determined to have a fully engaged life; or, Kittu deciding to have a little adventure on his own rather than being distressed about being left behind on a highway. And, we wondered how children were responding to this aspect in the books. It was not clear from children’s responses if they really picked on and thought about this aspect consciously or spontaneously recognized its importance.

Children did react, however, to the responses of the people around to the protagonists, and recognized supportive behaviors from that were not. “I loved her family, they made her feel so loved” a child said about Malathi’s family. In one group, they liked was how Mad treated Kittu – just like an equal, no special treatment. They noticed that adults behave differently with children with disability while kids behave differently – reference point being the manipulation of Madhav and over caring by Managaleshwari, Mad’s parents. When asked to compare with their own lives, one girl said, “So may be their parents were not as protective as ours and believed that could handle situations themselves.” In Kanna Panna, many children across groups pointed out that perhaps Kanna was diffident because of his over-strict parents, and equally strongly hated Rajat in Manya Learns to Roar for all his bullying while recognizing how sensitive and supportive their teacher Ms. Sridhar Ali and her friend Ankita were.

How Children Respond to Inclusive Books – Part 3

A very crucial aim of Parag bringing out more books with disability and inclusion as the theme is to encourage more conversations about individual differences,…

Inclusive Books & Children’s Response – Part 1

Do you know anyone with a disability in your family, community, school / organization? Take a minute to answer to this question…