Loading...

Loading...

‘Jamlo Chalti Gai’ is a translated book that was published in 2021. In English it was published as ‘Jamlo Walks’. A discussion around it is necessary for two reasons. One, because it brings up an issue that has been shied away from in children’s literature. Secondly, the responsibility, creativity and gravity with which this book presents the issue, brings tremendous hope for the field of children’s literature. Off late, amazing changes have been taking place in children’s literature, but this book is one step ahead. Supported by Parag, published by Eklavya, it has started a new discussion in the area of children’s literature publications.

Jamlo is a topic for a documentary. The way the story unfolds, page after page, showcases an excellent example of using cinematic craft to narrate a story. The writer of this book is a filmmaker and one can see her artistry very clearly in this book. Tarique Aziz, the illustrator, has transferred this artistry on paper with mastered control and balance. Along with the text, it is the strength of these illustrations that helps in taking this book to higher levels of experience.

On the very first page, the ‘camera’ focusses on a calendar page which shows the dates- 24th to 30th. There are red crosses on all these dates, signifying that days are being counted. This lone calendar hung on an empty, grey wall speaks of waiting… and sadness.

Next to the calendar is written: “It is day 7 of the Lockdown.” The announcement of this country-wide Lockdown on 24 March, 2020 was experienced by everyone differently- children-adults, rich-poor, urban-rural, everyone. But the calendar does not confine the dates to any month or year, thereby proclaiming this experience to be beyond time.

On the adjacent page, there is an illustration of a half-open window. It is evident, it is the month of March- outside, the sun is very bright; this half-open window makes it clear that only a balanced dose of heat and sunshine should enter the house.

Further, it is written: “and everyone says the skies are blue again”. It comforted many to think that plying of vehicles has stopped in this lockdown, factories have shut down and smoke and grime are absent, hence the sky is clear. For a few, this is the bright side of the Lockdown. The peace of being locked inside houses. Inside the house, there is a stability in the room. This scenario provides the backdrop of the story.

The very next page has the image of a child walking down the road: “Jamlo walks”, is the text with it. An innocence on her face, mixed feelings of worry and determination can be seen clearly in this illustration.

In the background of days being counted and clear blue skies, a child, all alone, has started walking in the blazing sun on a lonely, deserted road, with no signs of a shadow of a tree for miles. Whereas on the page just before it, near the half-open window of the room, a green potted plant complements the bright, blue skies. But for Jamlo who walks the long, grey road, it is the milestone that complements it. This is the beginning of a journey about which no one knows anything. It reads, “Nariapur 10”. But where is Nariapur, where is the final destination and how long must one walk to reach the destination, is not known.

The text further intensifies the gravity of this journey: “Jamlo wipes the sweat off her face and shifts the bag of chilies from one shoulder to the other”, as if by shifting the bag the feeling of burden will also change. The weight to be carried will remain the same, but shifting the weight to the other shoulder will change the way Jamlo feels the weight. Such false relief. Illustrations and text create movement in the scene and the reader feels as if Jamlo has actually just done that.

The scene changes. The text runs: “Amma is watching a video on the laptop of people walking”. It is a controlled setting, inside the room. There are books on the table, a green plant is blooming in the flower pot. The hand is on the computer mouse. A frame, that has to be used in the next scene, is ready.

Tara, a child, who has been peeping from behind the curtains, suddenly comes into the room: “Tara sees men and women carrying bundles and children looking tired and sunburnt.”

“When Amma notices Tara, she shuts down the laptop. The people walking disappear in a flash.” How well-controlled the situation is. Tara should not see a scene which disturbs her mind and makes it restless. A certain reality is taking place on the street, but seeing its video is also protected. Tara should not have to face an unpleasant video, that is why the hand is on the mouse, to make the scene disappear at will.

The text is: “walking people disappear in a flash.” Or are they made to disappear? The black and white curtain is drawn on the laptop to hide the reality. Now all is calm. There is no unpleasantness, no restlessness and no questions that might have been possibly asked. Now, Tara is at peace inside the house. Amma has shut down the laptop. The restlessness of the road is now gone, even from the laptop.

Amma asks, “Do you want dosa for breakfast?” There is a discussion on breakfast. It’s a relaxed day, which encompasses choices of watching or not watching a video, of options for breakfast.

But the very next frame is of Jamlo’s face. On a roadside stall, a child, three feet tall, is staring at a sizzling dosa on a five feet high tawa, as though she was seeing this for the first time. Having the dosa was out of question anyway, but this situation was also out of reach. Standing on her tiptoes, eyes wide open as she looks at the dosa, this illustration of Jamlo tells many stories at once.

“At the roadside stall, the man spreads batter on the tawa. It sizzles. Jamlo watches.” Not only is this sizzling felt on the tawa, but inside Jamlo’s stomach as well, even though not a word about it is said on these pages, but just from the way Jamlo is looking at it, one can feel the power of cinematic craft.

“She walks past a turn-off that says Tadvai 15”. While the earlier milestone said “Nariapur 10”. So, has the shorter aim of Nariapur been crossed, and is this now the next bigger goal? Where is Nariapur, where is Tadvai? No one knows. But the distance keeps increasing. There is another milestone ahead which says “Usur 20”. Is the destination continuously moving further away? The book doesn’t say anything about the destination, it only indicates through the number written on these milestones. This is the wonder of cinematic craft.

The road glistens in the scorching heat of March. “She sees figures swaying in the shimmer.” This is a Mirage. To Jamlo, it seems like an illusion of the Hareli festival, where people are dancing and singing, eating laddoos. These are life’s memories. A delusional thought that warms the heart amidst the anxiety of loneliness, helplessness, hunger, thirst and uncertainty. A fusion of reality and illusion, but for a few moments only.

“Jamlo blinks” as if she wants to shun the momentary illusion and gets ready to face the reality. “A car with a flag roars down the road.” This symbolises speed, authority and alacrity. Something that has no meaning for Jamlo, except that it is merely like a fast scene that quickly passes on.

“The road is still long and people are still walking.” For how many days will people keep walking – no one knows anything. Even more so for Jamlo.

The lines are: “Jamlo takes out her bottle of water that will soon be empty.” On the very next page, the lines read, “Aamir takes the bottle out of the fridge and pours out a tall glass of cold water.” One sentence and one scene set against another sentence and another scene, as if, there is a competition within the story to convey further. This is cinematic craft. There is no need to say much. On one side of the page, Jamlo is walking on the road, on the other side, Aamir is having an online class. “Then the sound becomes garbled and the communication is broken.”. On the next page, “Jamlo’s chappal breaks.” On one hand, there is much ado about the Internet connection breaking and this is also a relief, but on the other hand, Jamlo’s chappals coming apart, wreaks havoc within. In this arduous journey, if she has one resource, it is her chappal. Now the breaking of that chappal, is like the breakdown of her morale.

The lines are: “She is tired and thinks she will rest for a while. She lies down under the shade of some sal trees.”

We all know that she is tired and that she needs to rest. But the way these lines express this, they indicate something else as well. A doubt surrounds the reader. This gives us a glimpse of cinematic craft.

“They stand straight like soldiers.” Trees have become soldiers! For the last three days, soldiers standing upright on the roads and images of soldiers repeatedly stopping, refusing, scolding, standing around her, is like a hazy memory to Jamlo, who is lying down on the road.

“It is hard to stand straight when you have been walking for three days.” Jamlo is lying down.

Passers-by are heard saying, “They are saying corona kills… but bhai, so does hunger….” People who pass by have their own contexts; Jamlo’s context is also hidden among these. A film of memories is playing. “She thinks of a 600 years old tree somewhere in Bijapur that Pushpa didi had told her about… And what it feels like to be so old.” It’s a hazy memory.

“A yellow leaf flutters down on to her face.” A yellow, lifeless leaf falls. Right on Jamlo’s face.

“Jamlo shuts her eyes.”

The film of memories continues to play. Ma and Bapu rejoice when they see her. After earning a bag of chillies, she has walked so many kilometres to reach them. As if it’s a dream sequence/ she is dreaming. With her eyes closed, Jamlo lies there on the ground, like a yellow leaf.

“It is morning. Tara, Rahul and Aamir wake up to another day of online school.”

Another day of online school, another day of lockdown rules, another day when Jamlo is still on the road.

On the entire spread of the page, there lies one of Jamlo’s broken chappals and a yellow leaf.

“The skies are still blue, the road is still long, the people are still walking.” But Jamlo is not in the picture anymore. Instead of her, on the entire page is a broken chappal and a yellow leaf. This is the magic of cinematic craft that is able to convey with such subtlety and intensity, that the number on the milestone does not matter anymore. Jamlo’s parents standing at the door of their hut waiting for Jamlo and on the other page somewhere far away, a broken chappal and a lone yellow lifeless leaf, convey all that is impossible to say in any words. Samina, the writer and Tarique, the illustrator, have handled this with utmost care and patience.

Children’s literature is creating opportunities for such duets of text and illustrations that take the presentation of a book to very high levels. On the canvas of the Lockdown, this story of Jamlo is unfinished, even though it is over. Thrift of words and meaningful illustrations further deepen the restlessness that comes with this unfinished-ness, this incompleteness.

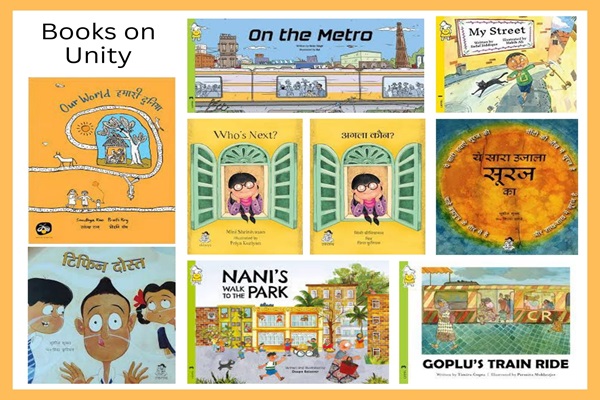

This National Unity Day on October 31st, read and discuss Parag books that celebrate the unique diversity of our country and the world at…

“In times of trouble, libraries are sanctuaries” – Susan Orlean, The Library Book.And so they are, at least in the pediatric cancer…